Photo courtesy Kehinde Wiley Studios

Photo courtesy Kehinde Wiley StudiosKehinde Wiley’s massive oil paintings cannot be ignored. The urban dressed African American males stare down from their place inside the canvas challenging you to turn your eyes away. “Look at me!” the paintings say, “I will not be ignored!” And I suspect Kehinde Wiley is content that he has caused the viewer to look closely at the role reversal he has created. For me, when I saw his work at the Portland (Oregon) Art Museum, I became transfixed.

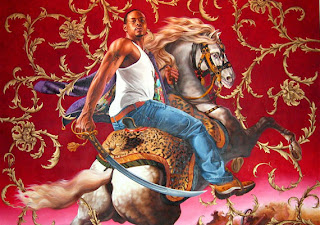

His paintings were hung on the top floor of the museum, on the far east wall. They were massive portraits of young urban-dressed African American males posed in the style of the Renaissance masters. The negative areas were filled with a delicate pattern, that somehow related to the subject of the work. Surrounding each portrait was a massive, intricately designed frame, similar to what would be found on a classical painting. What struck me were the images themselves. The men were larger than life, and posed in a way that when the painting was hung, the image would look down on the viewer in a smug, self assured way. Wiley’s work was detailed. Each portrait looked like a photograph. Each young man looked haughtily superior to the viewer.

I sat down to absorb the room. I was surrounded by Kehinde Wiley’s work. Why was I so fascinated? The detail was as real as one could achieve. But it was not only the detail. It was the unusual juxtaposition of young urban black men in their street clothes, posing as if they were famous subjects painted by the Renaissance Old Masters.

I had heard of people becoming affected by art, but it had never happened to me. Yet here I was, mesmerized by something so different, so beautifully executed, I had trouble pulling my eyes away. I felt as if I was in the room with greatness.

I wanted to more about the artist. His bio stated he was 30 years old, and had a Masters Degree in Fine Arts (MFA) from Yale University. Upon graduation, he had exhibited in some of the most prominent galleries in the United States. At 30, he was literally an instant success.

Kehinde Wiley came from South Central Los Angeles, one of the toughest neighborhoods in the area. His mother was aware of Wiley’s talents, and enrolled him and art classes where he excelled. He received a Bachelors of Fine Arts from San Francisco Art Institute, and his MFA in 2001. Scores of articles and interviews have been published on his “Hip Hop Art,” and he has appeared on television. When I heard that Kehinde Wiley was going to visit Portland and talk about his work, I could hardly wait to see him.

My initial impression of him is that he is not a tall man, has a soft, gentle voice, and is smart, and articulate on what inspires him and where he is going with his craft. With large projected images on a nearby screen, Wiley explained why he painted the way he did, and what was the purpose.

Throughout history, Kehinde Wiley explains, portraits were painted of famous or rich white men. They were depicted in their grandeur, many times along with their most valuable possessions. As a child, Wiley would visit museums and art galleries where the portraits of these powerful white men were shown. Wiley recalled one of the turning points in his career was when he saw Gainsborough’s portrait of The Blue Boy at the Huntington Library. The language of this portrait was a disturbing to him. He felt alienated; he could not relate to the image of a white, wealthy man.

In his research, Kehinde Wiley realized that the paintings of wealthy people were purposely distorted. He noted that the works by Titian and Tiepolo depicted the gendership of the subjects. The message had been codified to wealth and power--the wealthy would commission paintings where they would be draped in their finest jewels and dress in their most expensive clothing. The men would pose in a less masculine manner, yet still have the power associated with their wealth. In these Old Master paintings, external beauty was emphasized along with wealth. In fact, throughout history, gender and male beauty is abundant in paintings.

Wiley desired to create a statement that connected social adjustment, while keeping the integrity of the painting’s theme--money and power. He decided to transcribe Hip Hop and early Gangsta Rap into his version of a visual opera. When the Old Masters painted, they come from an era where the artists pushed the boundaries while placating the patrons. Wiley placed societal hypermasculine African American urban males in less masculine poses associated with these classical paintings. He pushes the viewer to consider the class struggle these portraits represent. Film producer, John Morrissey owns three of Wiley’s works. Morrissey believes, “[Wiley’s] engaging a cultural style associated with excess, where diamonds or bling become the status symbol that may have been a royal crest or emblem on a jacket in the past.”

These giants of history could also be mounted on horseback. For example, Kehinde has referenced David’s Napoleon Crossing he St. Bernard Pass with his Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps. What Kehinde Wiley found interesting, was that the equestrian figures were painted much larger than the scale of the animal. Here again, one witnesses the power of the individual who overtakes the powerful equine figure. And the animal itself is shown in a more effeminate fashion, with a delicate fetlock, and flowing mane. It is the juxtaposition of the masculine rider overpowering the feminine horse.

Kehinde Wiley not only realized the importance of masculinity in secular depictions, he noticed that religious-themed art elucidated the figures in a form of rapture; that light played a tremendous part in the illusion. He is continually pushing the boundaries and creating tension between figuration and decoration.

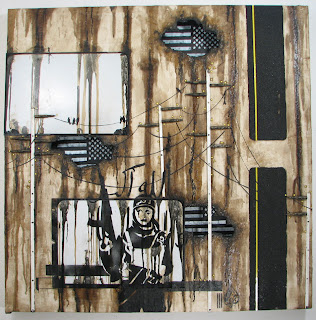

Wiley is also interested in wall paper, and how it is used in art during specific time periods. Some of the images showed the patron’s possessions behind him in a landscape formate. Other’s wealth was added as background elements of the interior scene. Wiley began to create a false world of flattened out space that was intricately detailed in a pattern that related to the history of the theme.

Massive frames that reflect the historical period are designed and placed around the portraits. In keeping with his masculinity theme, Kehinde Wiley uses sperm in some sections of both the frame and within some of the portraits, reducing masculinity to its basics.

His subjects are taken from the street and are between 18 and 34 years--the demographic age used to drive the cultural economy. They are selected because of their self possession. Kehinde discusses his idea with each one: that of using the subject as the centerpiece for a counter-culture viewpoint of great art. Wiley then gives the youth a book of classical painted images, and has him select which pose he would like to assume. If the selected subject model appears to be more aggressive, softer, gentler suggestions are shown.

Wiley has a team of apprentices working with him, similar to the Old Masters of long ago. His apprentices do most of the work, leaving Wiley the task of the portrait itself. The subject is photographed, and digitally altered. The backgrounds are painted as well as the body. The massive amount of work completed requires a large team of skilled craftspeople.

Kehinde Wiley has taken his Brooklyn, New York studio global and into China and the African countries of Dakar and Lagos. His most recent work outside the United States is in China, where he has imported African American models to assume the politically inspired classical Mao era propaganda art. In most of the poses, the models are smiling--an artifical-looking grin--to convince the population that the Communist leader’s rules are better than the old ways. Wiley has his models pose in exactly the same way, with grins. However, to show how artificial these grins were, Kehinde video taped the models grinning for 30 minutes. After a short while, the grins became forced. It was almost impossible to have a sincere smile. That is when the image was captured. There is a similarity between Eastern propaganda and that of the West, and Wiley wanted to show it using his Brooklyn models. African Americans from urban cities are beamed by satellite throughout the world and have become an international stage. The images used in his Chinese paintings question identity both locally and internationally. In his Chinese-inspired paintings, Kehinde Wiley incorporates the traditional Chinese textile backgrounds with lacquer frames.

Wiley now is considering the world as his studio, by bringing teams to work together. His African studio uses models from Dakar and Lagos. He is engaging the local population and including studies from the sculptures made during colonialism. The backgrounds will focus on the the patterns and colors of Africa, and the frames will be of local woods.

While he has certainly become an international sensation, fame has only given Wiley the opportunity to explore more areas of art and society. kehinde Wiley continues to push himself in territories where he doesn’t feel comfortable and, by doing so, challenges the viewpoint of what is acceptable culture.

All graphic images are used with the permission from Carrie Mackin of Kehinde Wiley’s studio, www.kehindewiley.com. I want to thank her for her assistance. For current information on lectures, exhibitions, and special projects, visit his website.