The Seattle native Jeffry Mitchell is excited and reflective. This June he celebrated two important events in his life: his half century birthday and his opening as one of five Pacific Northwest artists selected by the Portland Art Museum for their inaugural Contemporary Northwest Art Awards, a biennial awards exhibit that honors emerging and nationally under recognized professional artists living in the Northwest.

It’s been an interesting journey for Mitchell, who never saw an art museum until he moved to Texas to attend college. By his own admission, Mitchell grew up in a cultural vacuum. His dad worked for Boeing on military contracts, and the family traveled across the Northwest and Midwest to be near the bases. In these small towns of 30 to 40 thousand, there were no art museums. But that doesn’t mean he was not exposed to the creative experience.

His grandmother was a cultivator of Mitchell’s inner artistic voice. Originally from Minnesota, she moved to Seattle and married a Norwegian fisherman. Mitchell’s grandmother had her own business sewing for others, and that’s where Jeffry Mitchell learned to sew, knit, and crochet. He liked to work with his hands, and would make furniture. “Kinda crafty,” as he calls it. His work is still considered crafty by some. Being a gay kid, and living in the towns he lived in, shaped his imagination. If he hadn’t gone to art school, Mitchell admits he would have been a crafter.

But he did go. He majored in art at two very different universities. The first one was the small and very conservative University of Dallas, where he earned a BA in Painting. It was chosen without too much thought except that his sister received a scholarship there. With the second school, Mitchell knew he wanted to receive his masters degree in printmaking at an art school that was near the big art centers on the East Coast. He chose Tyler School of Art, Temple University in Philadelphia, for the proximity to the major museums, and because Tyler had a campus in Rome, Italy.

Because his family moved frequently, and spent all their time in smaller towns, seeing an art museum for the first time was a life-changing experience for Jeffry Mitchell. The museum was the Kimball Art Museum in Austin, Texas. He was, as he admits, “blown away” by the architecture, designed by Louis Kahn, as well as the collection. It all began to make sense. There was so much history. When he visited Philadelphia and Boston, he began to understand the impact of history on art and culture.

While at Tyler, Jeffry would frequent the galleries in New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C. Here is where he began to look at art seriously. He spent his second year at Tyler’s campus in Rome, Italy. Then everything fell into place. Rome was a giant art gallery, so full of history. He loved every second there. After graduation, all his classmates moved to New York City. Mitchell didn’t have the ambition at the time to live in New York. “It takes too much money, too much drive,” he stated. Besides, his large family (he has four brothers and four sisters) lived in Seattle. His friends were there, so Seattle became his permanent home.

Jeffry Mitchell didn’t expect to make money as an artist when he graduated from Tyler. He thought he would do “this” for a while, and not worry about what lies ahead. In reflection, not worrying was part of his immaturity, and it haunted him for a long time.

Mitchell remembers when things were financially pretty grim. One time he received an unrestricted $9,000 grant from the Banky Foundation; not a lot, but it made a huge difference to him. He was very low at the time, and this grant was a life saver. He paid off some debt, and got a cheap used car, because he didn’t have a car at the time. A car was crucial, especially carrying large amounts of clay. Unless its a lifestyle choice, Mitchell reflects, not having a car is demoralizing. He did what he had to do to survive, including manual labor to receive medical benefits for an old knee injury.

While recuperating from knee surgery, Mitchell heard of an opportunity to teach English in Japan, whose culture fascinated him. Mitchell fondly recalls his experiences teaching English at the cultural center in Nagoya, and studying ceramics. He lived in the small pre-war town of Seto which is the site of ancient kilns. The Japanese word for ceramics is either “yakimono” or “setomono,” a center for ceramics. Mitchell explained that the Japanese pottery foundation is based upon Korean potters who were kidnapped and forced into slave ceramic labor. Seto had numerous Koreans who had lived there for generations. He attended several tea ceremonies. The tea and ceramic heritage is based upon Korean customs brought over from those kidnapped Koreans. Mitchell reflects on his life in Japan and believes there is something remarkable about the tea ceremony, where one take the time to ritually consider the ceramics, the tea, the hospitality. To him, the traditional lifestyle seemed very civilized. Jeffry Mitchell shares a photograph of some work he did 20 or 30 years ago, and a recent magazine illustration on international culture. They are remarkably similar, and reflected his Japanese experience with its colors and shapes.

He first thought of himself as an artists in Japan. If someone asked him what he did, he replied, “I’m an artist.” The words felt right. Though he wasn’t making a living as an artist, he was learning ceramics, and working for a potter there. Surrounded by the simplicity of rural Japan, Jeffry Mitchell felt infused in the process of art. He remembers the procedures involved with ceramics there. How technically challenging, how labor intensive.

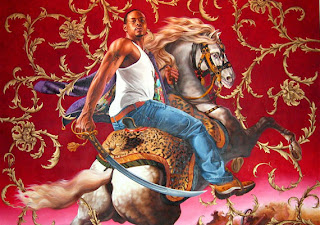

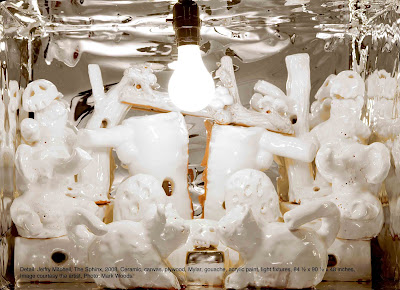

If he were to put a label on the style of work he produces it would be in the traditions of decorative and folk art, with a good dose of personal experiences. His work does have a crafty appearance, an homage to his childhood apprenticeship with his grandmother, and covers three major disciplines: printmaking, illustration, and ceramics. All are very detailed, with animal and plant motifs, a reflection of his Scandinavian heritage. Illustration, he believes, is challenging; there is an idea to consider before one begins. Drawing and watercolor are immediate, and he likes that. Ceramics are technically challenging because the process is long and involved, which can be tiring at times. Mitchell’s ceramic pieces are made up of numerous individual designed and fired plants, small animals, and the word “HELLO,” which is a societal way of communicating; sending a message for a response. Then there are his elephants.

His proclivity for elephants come from somewhere; but he is not sure. Babar, the fictional character created by Jean de Frunhoff comes to his mind. Dumbo, the floppy-eared Disney character is a favorite. But he is also fascinated by Asian interpretations of the pachyderm. In fact, Asia has a powerful force on him. Why?

While he doesn’t believe in it per say, he does think reincarnation is a good explanation why he has specific predilections and attractions to other cultures, especially Japanese. He loves the superflat artists, and specifically mentions a show curated in LA by Michael Darling, Seattle Art Museum modern and contemporary curator.

Most of his work is in white. When asked why white, he remembered when he was 18, and a student in Rome, he visited Switzerland. Robert Ryman [American b. 1930] had a show there. All his painting were white. “There must have been 40 paintings exactly the same size,” Mitchell recalls. “They were square. They were hung high. It was like heaven. Some people would say, ‘Oh my God, what is this?’ But I thought it was sublime. I thank that is one reason I use white. I think my own reason might be that I am kind of fair, it is somewhat self portraiture.”

Most of his work is in white. When asked why white, he remembered when he was 18, and a student in Rome, he visited Switzerland. Robert Ryman [American b. 1930] had a show there. All his painting were white. “There must have been 40 paintings exactly the same size,” Mitchell recalls. “They were square. They were hung high. It was like heaven. Some people would say, ‘Oh my God, what is this?’ But I thought it was sublime. I thank that is one reason I use white. I think my own reason might be that I am kind of fair, it is somewhat self portraiture.” Being gay, and coming out when he was 28 years old, has effected his process. He was “deep asleep,” as he remembers, perhaps because he was closeted for so long. His art is a reflection on his sexuality, and his desire to liberate himself on his uptightness about sex that is associated with his Catholic upbringing. Some of the images are visualizations he has while having sex. There are holes, which represent sphincter muscles, and penises are occasionally embedded and camouflaged in his intricate pieces.

Because the family moved a lot when he was young, Mitchell was never confronted by school bullies like most other gay kids. But it still makes him uncomfortable. He recently completed a residency in Knoxville, Tennessee, that was at a private school. Mitchell recalls, “The kids were great, but I still get tense when fourth grade boys beat up on each other in a friendly way, and call each other ‘faggot.’ I still get that ugh, crunchy feeling. In high school, it’s all about fitting in, and to be labeled a faggot was awful. People sometimes called me a sissy. But no one knew I was gay.” Everyone in his immediate family is accepting and loving. He has a niece that just came out. A sister is very religious and would prefer he not be gay. “She thinks,” Mitchell admits, “it’s curable or something, or a deficiency. Isn’t it funny? It is so sick, that you wouldn’t want everyone to be fully themselves like the wonderfulness of that.”

His selection for the award by the Portland Art Museum was through a process of a nomination by anonymous arts professionals in the area. The museum contacted different art pundits and asked for their advice, and he was nominated. Mitchell has a sketch of what he will exhibit in June. It is a cabinet of sorts, made up of stacked boxes, with a Northwest Native American design on the solid side. The opposite side of the box will be open and contain a lot of small white ceramic pieces inside. “One thing on one side,” he pointed to the sketch, “and one thing on the other.” Jennifer Gately, Portland Art Museum’s new curator of Northwest art, has seen the sketches, and knows what to expect. Mitchell is excited that he was accepted. The twenty-eight finalists received studio visits, and from that, they selected five artists. When asked about the studio visit, he said, “You know, it’s like a job interview, its hard to read.”

Though he is considered an established artist, Mitchell has always worked other jobs. He’s done manual labor, taught art at the University in Seattle, and taught English in Japan. For the past ten years, he has worked a couple of nights a week in a Seattle restaurant as a wait person. The owner was a student of his, and Mitchell has watched the restaurant become very successful and high end. Some of Mitchell’s work is in the restaurant, and he has sold pieces there.

He now thinks he can make money from his art. He is realizing what it takes to be a successful artist: believing that people want it; it is worth something; they will pay you money for it; and working with people who will sell it. Perhaps it was his time period in school, but Mitchell admits he used to have this distorted idea about art and money. “If you made things for the market, that was a betrayal of something.” He remembered, “But it’s okay, now. The Internet is changing the world.” He admits he needs a website, and he is in conversation with someone about that. “Everybody asks about your website,” he laments.

His advise for artists? Don’t go out on such a financial limb as he. Don’t be financially irresponsible. Twenty years ago there was more of a margin to live on the fringe, with a possibility to make money. It is important for everyone to make money, and there are different ways to make it. He has seen others become demoralized and ground down by years of living in poverty. He admits that he thought the poverty path was the freer path. Now he knows that is wrong. And, he advises, look at those who have succeeded. What got them there?

While in school, Mitchell didn’t get much mentorship from professional artists on what it took to make it in the art world. Nowadays, he reflects, they do have some classes on the business of art. The best lessons, he believes, are from those who have made it, not necessarily from a university job. While he had a great experience in art school, Mitchell has seen situations where artists have stopped doing art, have gotten into the educational system and have become bitter. They became anti-art. Having rotating, visiting artists, Mitchell reflects, is really a practical role model for the students.

He has gotten over the anger of someone who is making it as an artist with what he might believe inferior skills. “It doesn’t get you anywhere,” he states. What does amaze him is when he sees artists who work hard at their craft and are good, and who aren’t collected as widely as they should. It baffles him. However, he is not focused on the negative, he is focusing on making money.

There is room for everyone, he believes. The standard commercial gallery is not the fit for everyone. Things have really shifted, he admits. The gallery is still the focus, and its where people look. Criticism is broadly assimilated from work in a gallery network and institution.

Jeffry Mitchell is represented by two art galleries: James Harris in Seattle and Pulliam Deffenbaugh in Portland. How was he selected? They selected him, Mitchell shares, “That gallery thing is always by introduction. Cold calling never works that way. Someone they trust and respect says you should look at this work. They look at the work, and the relationship either goes or it doesn’t go.”

Jeffry Mitchell is having a remarkable year, and when his friends toast his birthday and his show at the Portland Art Museum, Mitchell can reflect that he has come a long way from small town hopping with his family. He has learned to collaborate more with artists, and to be more open and help others. Mitchell is all about community, and he is trying hard to help emerging artists. As an undergraduate, he had a powerful teacher who gave a lot of meaningful advise, but he wasn’t ready to listen. Years later, those words finally sunk in. It’s good, he believes, to have suggestions.